A Statement of Values by the new editorial board of The Psychoanalytic Activist

Dear readers,

We are writing to you as the newly formed editorial board of The Psychoanalytic Activist. In this initial essay, we seek to introduce ourselves as a board, and to share the guiding values which will orient our work as co-editors and help us to navigate this political moment. In alignment with the historical process of selection of editors, we were selected to be co-editors from a group of candidates who were presented to the executive board of Division 39 Section 9 of the American Psychological Association: Psychoanalysis for Social Responsibility. While two of us (Sinam and Drew) have worked together in other contexts, our third co-editor (Rodney) was suggested to the executive board by another colleague. As such, we found our first task as a group was to develop cohesion as an editorial board – finding the ways in which our visions and values align, as well as the ways in which our divergent experiences can be woven together in a work of co-construction. This piece contains sections that have been written separately by each member of the board, reflecting our own subjectivities and voices. Through this process, we have come to articulate a shared set of principles which we intend to guide our work as a collective.

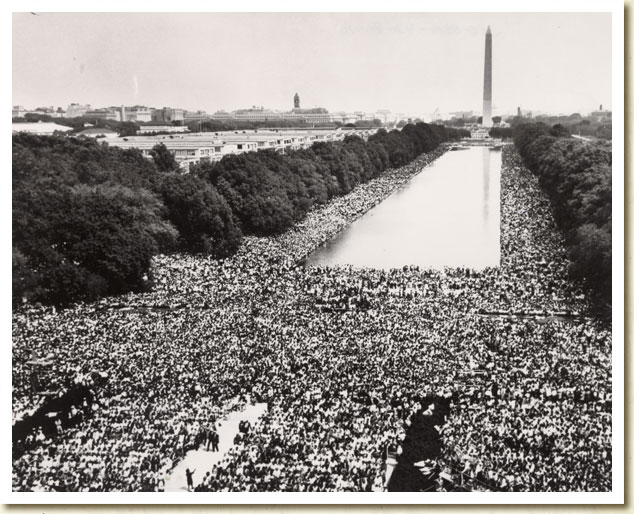

On this day in which we celebrate the life and legacy of Martin Luther King Jr., we are writing to you at a time of social and political reconfiguration – a time in which the social norms, institutional structures, and relational forms that have previously been taken for granted are being called into question. We are writing to you at a time when fascism and white nationalism are again moving into the open, seeking to exert ever-greater degrees of control and influence over the lives and minds of people across the globe. In the US, we see this white nationalist upheaval not as an aberration, but, rather, as a repetition compulsion – a re-surgence of the forces of violent oppression and white supremacy which have waxed and waned from visibility in the public sphere throughout our history as a country. In this time, when the aspects of this country’s history that it has sought to repress have returned with a vengeance, we are faced with difficult choices both as individuals and as a collective. As we encounter increasing degrees of dehumanization, and witness institutions of governance and social support being subverted in service of oppression and violence, we will likely feel our relationships being tested and our communities pushed to the point of breakdown, with neighbor turning against neighbor in the name of Law and Order.

Meeting within this social and historical context, we as co-editors have found ourselves faced with the question, “what does it mean to be a psychoanalytic activist in this political moment?” This essay is our own attempt to answer this question. We do not presume to be able to provide the answer to this question, but rather, are seeking to provide an answer, in the hope of spurring continued engagement and thinking in our larger professional, personal, and activist communities. We ask that you take this piece as an offering and an introduction – our own partial contribution to a collective struggle in which every one of us has a place. In this spirit, our first call for submissions will solicit your responses to this question, so that we can work together to expand understanding, forge connections, and build power through collective action.

Let us meet and work together to build our worlds of collective liberation.

We believe that being a psychoanalytic activist means:

To Center Relationships (Sinam Ward)

Being a psychoanalytic activist means to center relationships. At the core of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy is the therapeutic relationship – the way two people connect and make meaning together. Indeed, one of the greatest predictors of success in psychotherapy is the quality of the bond between client and clinician (Norcross & Lambert, 2018). Humans are inherently interdependent, and it is through our relationships – complex, messy, and full of contradictions – that we change, both individually and collectively.

Psychology, despite its imperfections, has long upheld values essential for collective transformation: a belief in the value of each individual, the importance of listening to one another, and the need for relationships as a foundation for learning and growth. As Lacan theorizes, language and identity are collective processes. He asserts, “It is the world of words that creates the world of things…man speaks, then, but it is because the symbol has made him man” (Lacan, 1966). We understand ourselves, our ideas, and our society in relation to others, which is why creating safe spaces for meaning-making and transformation is crucial.

The shift from a one-person to a two-person relational psychology in the 1970s and 1980s marked a significant turning point in the field of psychology. This transition moved the focus from intrapsychic processes (what happens inside us) to interpersonal dynamics (what happens between us) (Mitchell, 1988). Relational psychoanalysis views the therapeutic relationship as the arena where our attachment anxieties, defense mechanisms, cultural values, and core beliefs come to life. In these safe, dynamic relationships, we can lower our defenses, embrace vulnerability, deconstruct harmful ideologies, identify our needs and reclaim our power. It’s important to note that safety within a therapeutic bond doesn’t mean the absence of conflict or disagreement. In fact, research has shown that conflict or ruptures in therapy can lead to significant therapeutic change. These fissures allow the therapeutic dyad to deepen understanding of underlying dynamics and renegotiate trust (Safran et al., 2001). Therapy teaches us that in trusting, non-coercive relationships, we can reflect, experiment with new ways of being, and challenge each other in ways that expand our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

What makes centering relationships radical is that it counters the pervasive alienation in our society, which is fueled by the dominance of individualism. Centering relationships reminds us that we are collective beings, and we need relationships to thrive. Climate justice organizer Gopal Dayaneni, a founder of Movement Generation, emphasizes the necessity of interdependence for systemic change. At a National People’s Action community organizing conference presentation in 2014, he highlighted the truth that, in nature, the fundamental unit of life is dyadic and symbiotic – life itself requires interaction, and growth depends on support. No organism can survive or thrive in isolation. Community organizing requires us to cultivate strong, and dynamic relationships to build collective power and transform our reality. In this critical moment, with many of our communities facing repression, with the rise of fascism, and ongoing climate and economic crises, it is essential to prioritize the building of strong bonds, creating spaces for open communication and mutual support, and holding each other accountable for the change we need, both individually and collectively. We hope that the Psychoanalytic Activist can serve as a space to support this type of community building.

Another important aspect of nurturing relationships is – paradoxically – prioritizing our own well-being and needs. Individual and collective change exist in a dialectical relationship, requiring us to build new capacities both personally and as a community. Our ability to attend , as much as possible to our basic needs, process grief, and cultivate joy amidst systemic injustice sustains us as we continue the fight for radical change. Furthermore, our commitment to personal growth can strengthen the collective as a whole. We aim to spotlight work that embraces both sides of this dialectic, recognizing the necessity of finding new ways to care for our minds, bodies, and spirits to face our current conditions.

To See (Drew Madore)

To be a psychoanalytic activist also means to see – to apprehend the intrapsychic and relational dynamics that perpetuate processes of entrenchment and of transformation. In the seeing, there is also the naming of these dynamics, and in naming them, they can be brought into the light so that we can work to transform them.

To see in the psychoanalytic sense is also to attend to that which continually works to remain unseen – to identify the dynamic forces at work not only by what they show, but also by what they foreclose. In this, the psychoanalytic act of apprehension is not merely a singular event, but rather, an ongoing process requiring the continuous maintenance of conscious awareness in an effort to resist the internal and social-relational dynamics that function to occlude the reality of what is unfolding around us, within us, and between us. It is these dynamics of occlusion – repression, foreclosure, and disavowal – that continuously operate at the individual, relational, systemic, and social levels and allow oppression to flourish. Psychoanalysis offers us another insight: that tending to consciousness as an ongoing act – always imperfectly conscious and partially perceived, but invariably instructive – is aided by dialogic encounter with another. In this way, to see and to relate psychoanalytically are two dimensions of the work which are never complete without the other.

To see psychoanalytically is also to make links: links between past and present, self and other, and internal and sociopolitical worlds. Psychoanalysis offers us a framework through which the processes that operate at the internal, relational, social, political, and systemic levels can be drawn into connection with each other (Rasmussen & Salhani, 2010). Indeed, it is this ability to make links which allows us to bring attention to the workings of power which seek to remain invisible, and to see the dynamics that lie beneath the surface which uphold the current organizing structures of oppression that function to distribute both gain and suffering unequally, unjustly, and unquestioningly. In the words of Russel Jacoby, psychoanalysis helps us see “the social process that shapes human existence into its prevailing configuration: inhuman for some and human for others” (Jacoby, 1997).

In this current political moment, we will face – collectively – the temptation to not see, to turn away from the pain of the other and the pain of knowing the ways in which we are implicated in the oppressive structures that perpetuate the violence upholding our daily lives. In this, to see psychoanalytically also requires a confrontation with that which we would disavow from within ourselves – the capacities for violence, to do harm, and to subjugate the other for the sake of the self.

This act of seeing, too, is one which must be employed at the individual and collective levels. It is not enough to identify the capacities for harm within the individual, for in doing so, we mistakenly uphold the fascist fantasy that if the “bad” individual can be identified, then they can be expelled, so that society can retain its supposed purity, and the fantasied goodness of the self need not be questioned (Loewenstein, 2023). Through this process, we take the “bad” and unwanted parts of the self (Sullivan, 1953) and project them onto others, most often onto groups of people that are marginalized and otherwise deemed to be “undesirable” members of society. Rather than giving in to this projective process, we must continually retain the awareness that any badness identified within an individual is inextricably linked to the violence of the society in which we live, and that the evil we see in the other also exists within ourselves – that the violence of the world in which we live has been built by us, collectively. This act of seeing, too, is one in which dialogue and the relational co-construction of understanding is vital, for no single person is capable of seeing all the dimensions of violence and its roots. There will always be some individuals who – as a product of their social position and degrees of conscious awareness – will have the capacity to see something which others cannot.

A psychoanalytic ethic puts forth the moral imperative to continue to endeavor to see the truth about ourselves and the world as it is, and not as we would wish it to be (McWilliams, 2004). To address this difficulty, a psychoanalytic praxis offers reflective and relational processes through which we can combat the dynamics of disavowal, subjugation, and alienation in the struggle toward collective liberation. In the Psychoanalytic Activist, we seek to create a space for seeing, naming, and linking. In the spirit of dialogic encounter, we aim to bring together voices and experiences of people who engage in liberatory work through a variety of reflective methods and practices – methods which include psychotherapy, but also extend to encompass community organizing, public education, and other practices of consciousness-raising and psychosocial transformation that occur outside the confines of the therapy office.

To Make Meaning (Rodney Orders)

To be a psychoanalytic activist requires us to be willing to be labeled as “bad” in order to promote change and provide corrective experiences. We must shed conformity to oppressive ideologies in order to make meaning in a new way. Preserving ourselves as “good” at the cost of speaking truth to power is more often a symptomatic compromise of self than it is a strategic choice. In a world that marginalizes and oppresses those who society would like to abandon and forget, we must support and defend those society despises. As Martin Luther King said, “The time is always right to do what is right.”

When we begin to contemplate the world in which we presently live, we must forgo the idealized world we may have grown up in, where what was moral and ethical was thought to be centered around democratic values. Today’s democracy more overtly weaponizes and rewards cruel, amoral, and unethical behavior. Contempt and resentment have taken center stage. The perpetrators of harm in this fascist, authoritarian experience we now call the American dream have claimed the status of oppression and marginalization for themselves in a gleeful perversion of the truth. While oppression and marginalization undeniably dominate our social and political spheres, it is those who most loudly protest their own imagined “extinction” who most fervently seek to purge anyone different from them, protesting their own acclaimed oppression while actively oppressing others. We are living in a fascist world now. We can no longer ignore, disavow or discharge this fact. We must accept this and try to make meaning of it.

At this moment in history, all hands must be on deck. We must resist, listen, and make meaning of this moment despite the real threat from the political Right to hunt, target, and silence those who oppose a fascist agenda. We must give voice to the grievances of our ancestors and speak the unspoken dread to air our grievances in an attempt to create a better world for tomorrow. I believe it is possible to de-center and destabilize individual life experience to break down those systems which provide comfort and status to those who harm the oppressed and marginalized in the world. As activists we must favor community over individualism. We must work through the contempt and resentment between us to find collective liberation. To ignore this would lead to more division amongst us.

I believe Psychoanalysis provides the technology to collectively liberate us from fascism. Fascism thrives on the repression of desire, diversity and creativity in favor of collective conformity. Fascism thrives on the suppression of individuality and critical thinking. In Escape from Freedom (1994), by Erich Fromm, he links Fascism to a society that is overwhelmed with freedom and the isolation and anxiety it creates. He argues that people escape freedom by surrendering their autonomy to authoritarian leaders to avoid the challenges of freedom. Fromm argues that true freedom requires self-awareness and the courage to embrace individuality, and that a healthy society fosters creativity and self-expression. Psychoanalysis which, when embodied, can empower the collective to listen, dialogue, and work through conflict which are crucial for making meaning out of complex realities and maintaining democratic social systems.

During Freud’s time, sex was taboo to speak of in public. Sexual drives were repressed to maintain order in a society that imposed strict rules on individual sexual freedom. That tension between a liberated self and the maintenance of a social order is the price individuals pay as we seek to live in harmony with one another. In our time, addressing racism, fascism, heterosexism, and gender binaries is taboo. Psychoanalysis provides interpersonal and intersubjective theories to help us know what we are not supposed to know about the other. It allows us to speak those taboos to one another in therapy rooms across the world. Those theories also help us organize experience and co-create meaning. They help us de-center ourselves to consider the other.

Although these theories usually limit the experience to the intersubjective field, I would argue that there is potential for an expansive field view that allows for the collective to be considered. In an expanding intersubjective field, corrective experience can go beyond the consulting room. Psychoanalysis practiced in this way is about the larger community and society. To make meaning acknowledges the human condition beyond the consulting room – the sociocultural and political context in which we live.

There is something about the power of community that is healing and corrective. According to Sullivan (1953), “No matter how much human individuals differ from one another these differences are minuscule…our weaknesses, no less than our virtues, are human weaknesses.” Being in community and recognizing that we are much more similar than our perceived differences is more corrective than being with oneself in an isolated echo chamber. Community is that symbolic parent who holds and meets the need of the self so that “good me” can emerge. Community is empathic and can allow for disjunctive dialog. Controversial conversations about the “something we are not supposed to know” about the other can take place in community; conversations such as “we the people created the fascism we know live in, because we feared to be free.”

Doris Brothers and Jon Sletvolds’(2023) book titled Talking Bodies discuss a theoretical concept of I, You, We, World. This theory uses embodiment as a way to make meaning of the flow between these different dimensions of human attention. In taking on the idea of fascism, they state, “at times of great societal stress, a sense of we, for some people, may be based only on sameness. This we, then, becomes “us,” and all others who are not experienced as the same as us become ‘them.’” At such times, our embodied feelings change dramatically. When we feel connected to those we view as “us,” we tend to experience a sense of calmness, safety, openness and even, at times, elation; when viewing ourselves with respect to those we consider “them,” we tend to experience fear, hostility, and withdrawal.

If we center community, I believe “We-ness” prevails because there is the possibility for embodied connectedness. What makes us the same and what makes us different commingle and converge to create meaning of experience. “We, World” is about being activists in an embodied community. It is about understanding the history that led to this moment of fascism. It requires all that is expressed and unexpressed. All that is felt and not felt. All that is seen and not seen. All that is said and not said. It is all that we are and what we will ever be.

We make meaning that takes on the World when we as activists, analysts, patients, and community oppose, defend, and resist together.

To Act and Disrupt (Sinam Ward)

At the heart of psychoanalytic activism is liberation, which requires us to act. As activists we are called to disrupt the logic and harm endemic to the systems of capitalism, heteropatriarchy, and racism. We are also called to create new ways of relating to ourselves, one another, and the world that promote growth, freedom and safety. In our view, liberatory action requires both deep reflection and political action, or praxis. As Freire (1970) states, “praxis is reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it.” On the individual level, psychoanalysis and psychodynamic therapy is based on a type of praxis. We draw on theories of human behavior and internal processes, based on clinical observation and research, to support clients in reflecting on their experiences, deepen insight, and consider new ways of engaging the world. Defining ourselves as activists calls for us to apply this methodology on a systemic level. We must utilize praxis to understand and address the problems we face on multiple levels: within the mental health field, in our communities, nationally, and internationally, as they are all interconnected. Without moving beyond the therapy room, we remain trapped in perpetual cycles of violence that produce the trauma and destruction that we so desperately desire to heal from.

Despite the necessity of engaging in political action, there exist many barriers on the personal, interpersonal, and social levels to address social issues. Winnicott helps us to consider the ways in which the fear of breakdown may prevent us from confronting the reality of violence and pain we have experienced, leading to cognitive dissonance. He describes this terror as a fear of reliving the past and opening old wounds. He states, “I contend that clinical fear of breakdown is the fear of a breakdown that has already been experienced. It is a fear of the original agony…” (Winnicott, 1974). Addressing and confronting personal and collective trauma requires us to go back to painful events, sit with unbearable emotions, and allow this process to transform us. When we open ourselves up to the depth of violence we experience both presently and historically, we face the possibility of overwhelm and disorientation. Winnicott suggests that we may resist exploring or knowing these parts of ourselves and our world. Additionally, because psychoanalysis necessitates confrontation of painful truths, it may be viewed by some as disorganizing or disruptive. It is true that without safe containment and skilled facilitation, confronting trauma, whether individual or collective, can lead to further dysregulation and possible harm. However, in a healthy therapeutic relationship or other supportive container, breakdowns can make way for profound change. Bion (1965) uses the concept of catastrophic change to highlight how difficult realizations – that can be felt by the individual as cataclysmic – can lead to growth because confronting and dismantling of old ways of being and understanding ourselves in a new way, allows us to rebuild our identities, worldview, and lives in a way that aligns with continued transformation.

We believe that this moment requires us to utilize academic and political organizing platforms to reflect and act in powerful ways together that address the roots of the suffering we are collectively experiencing. In particular, it is imperative that we utilize praxis to transform the mental health system, which continues to perpetuate violence through corporatization, classism, racism, sexism, homophobia, and other harmful ideologies, and also repeatedly fails to connect radical theory and action in meaningful ways. Freud himself acknowledged the validity and inevitability of collective action under oppression, stating, “It goes without saying that a civilization which leaves so large a number of its participants unsatisfied and drives them into revolt neither has nor deserves the prospect of a lasting existence” (Freud, 1927). We must move beyond philosophy, beyond therapy, and beyond patient/expert hierarchies to fight for a world in which healing and safety is possible for all. As Marx (1845) states, “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.”

References:

- Bion, W. R. (1965). Transformations. London: William Heinemann Medical Books.

- Brothers, D., & Sletevold, J. (2023). Talking bodies: A new vision of psychoanalytic theory, practice, and supervision. Routledge.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). Herder and Herder.

- Freud, S. (1927). The future of an illusion. Hogarth Press.

- Fromm, E. (1994). Escape from freedom. Henry Holt and Company.

- Jacoby, R. (1997). Social amnesia: A critique of contemporary psychology. Transaction Publishers.

- Lacan, J. (1977). The function and field of speech and language in psychoanalysis. In Écrits: A selection (A. Sheridan, Trans., pp. 30–113). Norton. (Original work published 1966)

- Loewenstein, E. A. (2023). In dark times: Psychoanalytic praxis as a form of resistance to fascist propaganda. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 43(2), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690.2023.2163150

- Norcross, J. C., & Lambert, M. J. (2018). Psychotherapy relationships that work III. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000193

- McWilliams, N. (2004). Psychoanalytic psychotherapy: A practitioner’s guide. The Guilford Press.

- Mitchell, S. A. (1988). Relational concepts in psychoanalysis: An integration. Harvard University Press.

- Rasmussen, B., & Salhani, D. (2010). Some social implications of psychoanalytic theory: A social work perspective. Journal of Social Work Practice, 24(2), 209–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650531003741728

- Safran, J. D., Muran, J. C., Samstag, L. W., & Stevens, C. (2001). Repairing alliance ruptures. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(4), 406–412. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.406

- Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Winnicott, D. W. (1974). The fear of breakdown. In The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. International Universities Press.

Essosinam “Sinam” Ward (she/her) is a Black mixed-race cisgender queer woman and clinical psychologist committed to personal and collective transformation. She received her doctorate from Adelphi University in NY. Through clinical work and community organizing, she seeks to build relationships and promote dialogue between social movement spaces and radical mental health. She finds resilience through nerding out on evolutionary biology, being in nature, dancing, and making and trying new foods.

Drew Madore (he/they) is a white, queer-man and clinical psychologist who believes that collective liberation entails the dismantling of hegemonic ideologies and the reflective restructuring of modes of being at the individual, relational, and systemic levels. In restructuring, there is fluidity, and within fluidity, the freedom of continuous evolution. Drew works in a community mental health setting, specializing in working with adolescents and emerging adults living with experiences commonly labeled as “psychosis”. Within their work, Drew is enlivened by the depth of connection that is the grounding of relational work, and the beauty that can be found in the mystery and complexity of the life of the mind. Outside of work, he finds joy in connection and play – be it in tabletop games, disc golf, or dancing to whatever song makes his heart sing.

Rodney Orders (He/Him) is a black cisgender queer man and clinical social worker who graduated from the University of Maryland at Baltimore in 2003. He is a member-in-training in the Psychoanalytic Training Program at the Institute of Contemporary Psychotherapy & Psychoanalysis. Rodney works full-time in private practice in Rockville, MD and is a Employee Assistance Counselor for ABC News Washington Bureau. In his spare time he likes traveling, hiking, and having conversation.

One response

[…] The Psychoanalytic Activist is our online publication, and the current editorial board is seeking submissions in response to the question: “What does it mean to be a psychoanalytic activist in this political moment?” The editors have posted their own response to this question, which can be read here. […]